____________

In September 1985, veterinarian and long-time United States Department of Agriculture meat inspector Carl Telleen penned a letter to his former USDA colleagues: “To my former fellow Review Officers,” he began, “It has been a most painful experience for all of us but one which we had to suffer in order to maintain our own integrity as well as to be able to expose the evils in government.” [1] The painful experience to which he is referring is a four-year battle between Telleen, the USDA, and the conglomerate of companies making up the lion’s share of the modern American meatpacking industry. In 1981, after serving for 20 years as a meat inspector, Telleen charged the USDA with instituting meat inspection policies that broke longstanding food safety laws and endangered the public. To his view, these changes were made for commercial and political reasons at the expense of public health. By 1985, Telleen’s whistleblowing campaign, steeped in acrimony and intimidation, had brought him national notoriety and made him a polarizing figure in the agricultural veterinary world. When the USDA deregulated its inspection policies, he was horrified that the public would consume contaminated meat, and lost faith in the government’s role in protecting citizens from harm. To Telleen, the principles of American democracy were centered on healthy meat, and both were at risk.

Carl Telleen became a veterinarian in 1937. He ran a private practice for agricultural animal medicine in Iowa, a growing hub of industrial pork and poultry, for over twenty years before becoming a USDA meat inspector in 1961. He spent the mid-1970s and early 1980s as part of an inspection review team, travelling across the United States to review inspection procedures at over 1500 plants over a span of eight years. During his tenure as a reviewer, the USDA loosened the definition of “contamination” in its Meat and Poultry Inspection Program to benefit corporate producers. With this change came adjustments in slaughterhouse procedure, which had been governed more or less continuously by the Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906.

One of these adjustments was to allow for a certain amount of contaminated meat to remain in the food supply — a margin of error not allowable by law. This change was justified by an argument for efficiency: in order to meet increasing demands for an ever-growing number of processed carcasses per hour, such stringent contamination provisions were no longer tenable. In 1974, the poultry industry sought to loosen regulations at the evisceration station, where most inspection-related delays occurred. For example, if the delicate intestinal walls ruptured while cleaning the cavity, bringing fecal matter into contact with flesh, inspectors at the station were legally required to condemn the meat. In 1977, the USDA published the results of a contamination study in the Journal of Food Science, which found that the evisceration station was the main obstacle to greater plant efficiency. This study propelled poultry packers to lobby the USDA for change. By the early 1980s, the USDA relaxed its inspection procedures at the evisceration table, adjusting regulations “to permit fecal contaminated carcasses to be washed until they appeared clean and sold into commerce” and relaxing inspection protocols “to permit a large plant to produce as much as 28,000 #’s to 36,000 #’s of adulterated product per week” without being shut down by USDA inspectors. [2] The effect of this discrepancy was that federal veterinary inspectors were no longer able to flag all fecally contaminated meat or to shut down plants for violating contamination standards according to the law. The USDA therefore changed its regulatory policy to address the demands of efficiency, but did so in violation of longstanding laws.

|

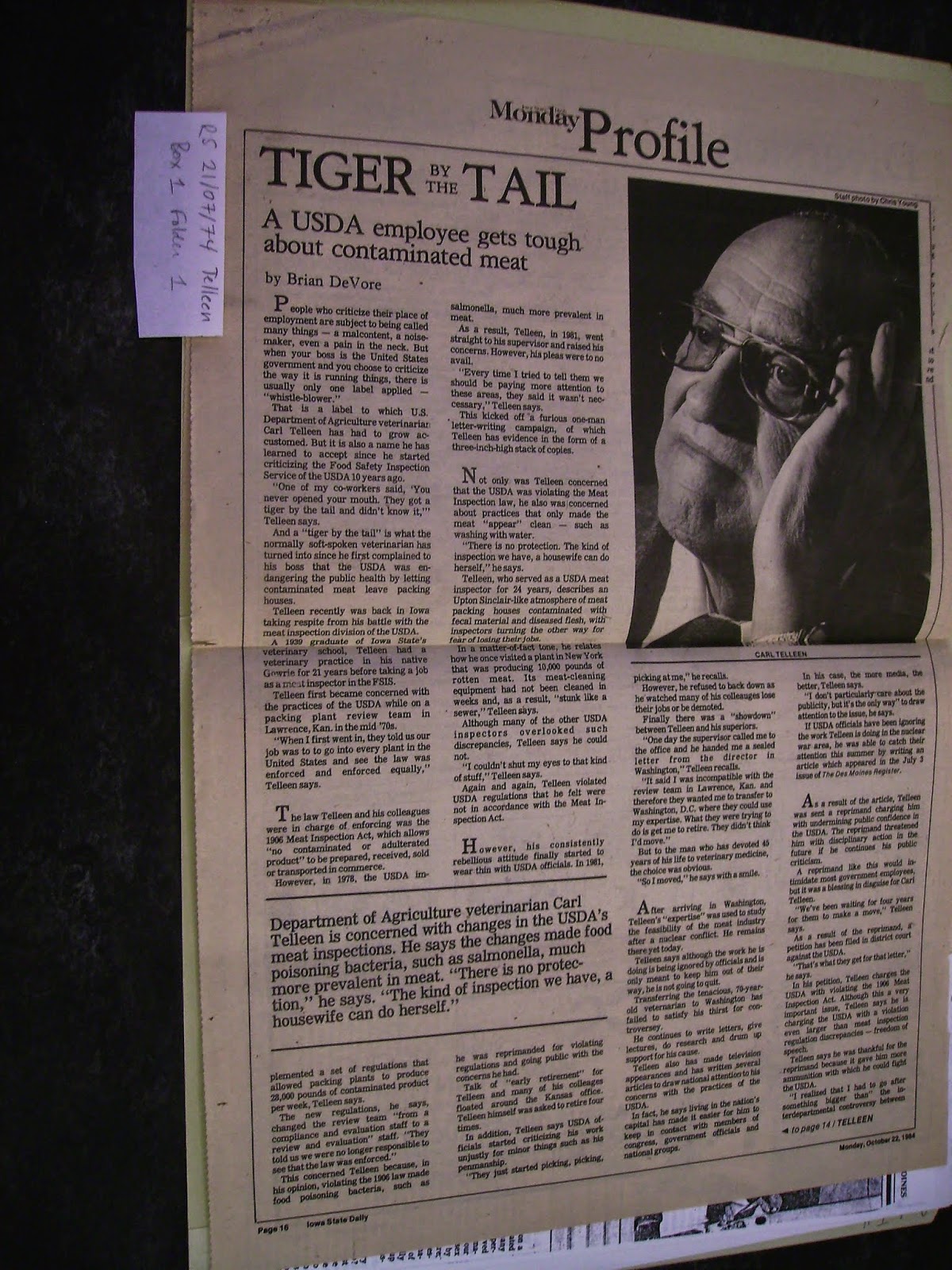

| Fig. 1. Des Moines Register profile of Carl Telleen. [7] |

USDA deregulation and Telleen’s whistleblowing campaign had an immediate impact on veterinary inspector employment. In a 1982 letter to the president of the American Association of Federal Veterinarians, Telleen warned that “Scientific positions that should be filled by veterinarians are being filled by union member, non-scientific, lay inspectors” despite the fact that “the taxpayer supports universities for the purpose of preparing veterinarians to protect the food supply.” [4] In 1983, federal veterinarians in Arkansas published an editorial in the professional periodical The Federal Veterinarian, stating that their jobs had been threatened when they refused to allow fecally contaminated chicken — which they described as having “been bathed in a ‘fecal slurry’” — to pass inspection. They wrote, “Field veterinarians are becoming increasingly frustrated, and even humiliated by the manner in which our responsibility and authority for implementing the agency mission…has been undermined.” [5]

Telleen collected individual accounts from veterinarians who detailed the efforts of the USDA to curtail thorough inspections. This letter from Dr. Ruth Blackburn (Figure 2) is typical in its account of the harassment and intimidation she felt as the USDA coerced her and her colleagues into “rewriting our reports to downplay the defects and violations that we saw in the plants that we were inspecting” or “look for jobs elsewhere.”

|

| Fig. 2. Affidavit in support of Telleen from Dr. Ruth Blackburn. [8] |

In 1985, Telleen won his only victory in this fight when the Government Accountability Project launched an investigation into the USDA’s abuse of deregulatory policies and harassment of veterinary inspectors. Yet despite the numerous affidavits written by fellow federal industrial veterinarians who testified that his campaign addressed the widespread contamination of meat and concurrent intimidation of inspectors, this is where his campaign ends. No action was ever taken against the agency, and resultant deregulatory policies stood. For Telleen, this change was more than a matter of structural readjustment: it was political. Telleen argued that the relationship between meat and democracy was direct, writing in exasperation, “It seems when a nation loses its democracy, the public will just have to eat adulterated meat and poultry products and pay taxes to help industry disguise it.” [6] The singular point of contact between flesh and waste expanded to contaminate the relationships between industrial agriculture and public health. Though Telleen was a persistent and uncompromising whistleblower, the deregulation of USDA’s inspection policies became standard to industrial processing procedure, severely compromising veterinarians’ ability to advocate for industrial animals, and for human and animal public health.

________________________

[1] Papers, RS 21/07/74, Special Collections Department, Iowa State University. Correspondence, Box 1 Folder 3, Carl Laurel Telleen Papers, RS 21//7/74, Special Collections Department, Iowa State University.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Clipping from the Des Moines Register, Box 1 Folder 1, Carl Laurel Telleen Papers, RS 21//7/74, Special Collections Department, Iowa State University.

[4] Correspondence, Box 1 Folder 3, Carl Laurel Telleen Papers, RS 21//7/74, Special Collections Department, Iowa State University.

[5] Testimonials, Box 1 Folder 4, Carl Laurel Telleen Papers, RS 21//7/74, Special Collections Department, Iowa State University.

[6] Telleen, “Abuse of Government Within the USDA: A Threat to the Family Farm,” Box 1 Folder 2, Carl Laurel Telleen Papers, RS 21//7/74, Special Collections Department, Iowa State University.

[7] Figure 1: Clipping from the October 22, 1984 issue of Iowa State Daily. Box 1 Folder 1, Carl Laurel Telleen Papers, RS 21/07/74, Special Collections Department, Iowa State University.

[8] Affidavit in support of Carl Telleen, August 26, 1985. Box 2 Folder 4, Carl Laurel Telleen

2 comments:

We have committed and experiences staff and they a trained on a regular basis on the importance of food hygiene and food manufacture. Read more Majestic Meat Ltd Unit 2-3, Crossley Hall Works York Street Bradford BD8 OHR T: 01274 544675 W: www.majesticmeat.co.uk E: info@majesticmeat.co.uk hmc halal meat suppliers

This is an important and timely discussion about public health.

Post a Comment